Apocalypso

Revisiting two MIT/Goldsmiths books for our time

Steve Beard – Six Concepts for the End of the World (Goldsmiths/MIT)

Charlie Gere – I Hate The Lake District (Goldsmiths/MIT)

Both these books are part of the Goldsmiths Unidentified Fictional Objects series (UFO) and both of them are absolutely bang on the times we are in.

Both these books sit inside the declared age of the Anthropocene without directly discoursing on it. The Anthropocene – for all it has contributed – leaves us in an empty place which calls on us to leap to where buddhist total acceptance and total nihilism are pooled. Both are not solid substances, but jumping in every day is the only way to live here, in this place with no floor. This, in fact, is what we all do every day now, whether we recognise it, refuse it, accept it or embrace it.

Perhaps we deserve to be there. But surely to say ‘deserved’ is to recourse to an earlier Western age with its solidified Christianity, morals and divine justice. That ‘deserved’ rattles straight out of my keyboard via automatic hands tells me that many of us still live in that earlier time.

But we’re all entering the new age, whether we like it or not, the rise of the dystopian as mass consumer entertainment tells us this: we take our disturbing missives from a future we are actually in as pleasurably as we can. Here are two more ways:

Charlie Gere’s I Hate The Lake District hits a particular nerve. We used to head up there often when I was young, me and my parents, camping, walking. In my early teens I discovered Jerry Cornelius paperbacks and a line still sticks with me in which Jerry/Michael Moorcock withers Wordsworth and the Lakes.

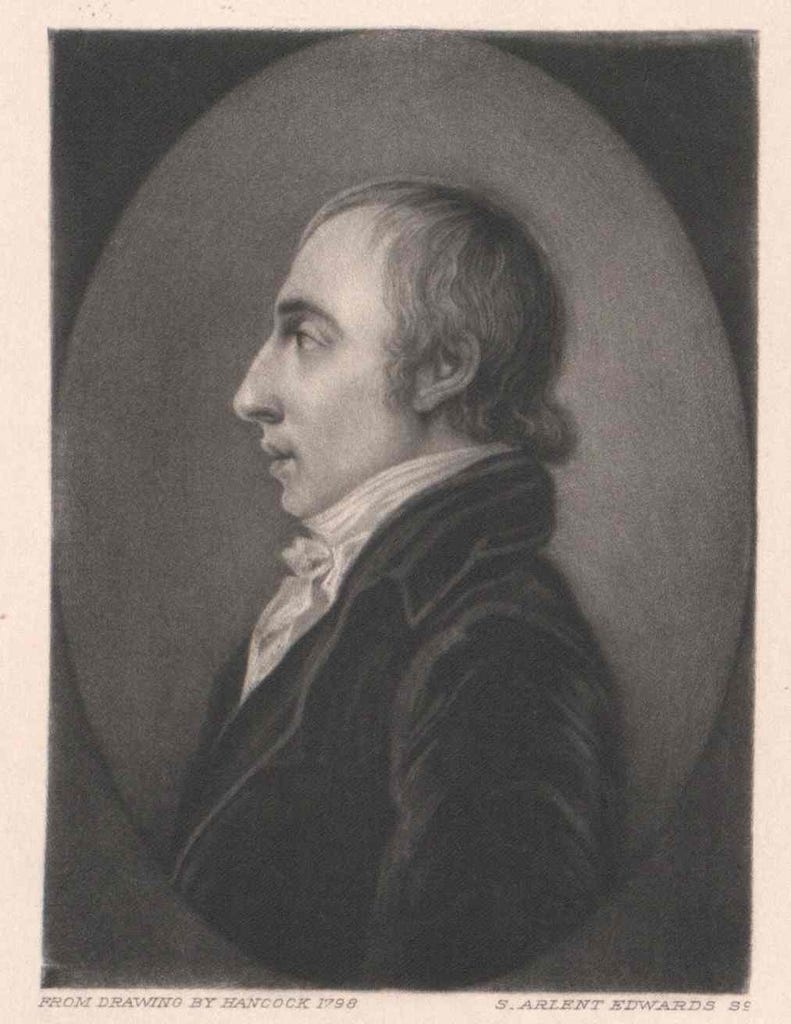

Wordsworth’s idea, that nature exists for man, that it completes man, died with him. Nine years after his death Origin of the Species was published. Marx’s Capital followed soon after. If we now live between buddhism and nihilism, the romantics lived similarly - but more tautly - between enlightenment and resistance to its instrumentalising aspects.

How quaint that seems now. How much I want the – yes constructed – Lake District of sweeping vistas and mountains now. How much I want the – yes monetised – Lake District of swimming, walking and leisure now.

Suddenly, I want to never have read cynical Jerry Cornelius paperbacks, or any philosophy, to be dumb, dumber and to have lived an unintellectual life with regular visits to ‘the picturesque’. It is far too late for all that. The older me was murdered by his own brain a long time ago. So, probably, was yours.

But I resist, as the author drives through a Lakes as a kind of cinema, although I like that he doesn’t fetishise walking and says so, I like that a lot, but I realise that a few months ago I wouldn’t be resisting his narrative at all.

He goes to Furness and Sellafield. To Briggflats via Basil Bunting, of course, and George Fox the Quaker. But there it is, lurking, British Intelligence, BAE systems, under the surface, always, WW2 and the Cold War. It will raise some heckles and is calculated to do so, but this era was surely furthered in Austria, another supposed ‘beauty spot.’

This is a Lake District of Tarkovsky’s Stalker and Ballard. But Gere’s book is much bigger than even that, bigger than the psychogeography diaspora too. It examines a world that five minutes ago seemed taken for granted, solid, eternal, as now just a brief cosmic weather shift.

I’m re-reading John Gray’s The New Leviathans (Penguin) at the same time. Partly a return to Hobbes to explore the work, partly an attempt to understand the new political landscape. He understands it like Gere does, but focusing much more on our emerging post-liberal vistas. Gray understands Russia’s implosion will bring huge risk. The meltdown of such a huge territory with the world’s biggest nuclear arsenal at its centre. I can read Gray’s book in parallel with these two. And you know, we can mutter about Gray, but he’s a good writer to spar with.

Steve Beard’s Six Concepts for the End of the World fits in flush with the Gere and Gray, even though it’s more an experimental fiction work. The main character takes a job inspiring techies and drone scientists. He is an artist whose career is in ‘terminal decline.’ His companion is a man called Haubenstock, I can’t stop thinking of him as a kind of tough German shoe. The prose is in that lineage of Kotting, Keiller, Petit, Sinclair (although gladly with none of his purple haze).

Our team of artist slash budget tax write offs decide to model the end of the world for the drone scientists. They mine Virilio. The disaster scenarios pile up. They are all essentially science fiction, in a world in which sci-fi often becomes everyday. Paragraphs in Beard’s book leap off the page because they seem to be happening already. It is not comfortable.

But I am equally interested in the way these narratives fall out of their creator in the same way ‘deserving’ dropped out of me as I wrote this review. I am even more interested in the fact that this kind of disaster speculation has become a kind of everyday prophecy across the world for some - and these thoughts of mine have not been fully processed.

Since this book was written and published, people have protested that Huawei’s 5G masts are actually pumping SARS-CoV-2 out into the air and into our bloodstreams through our eyeballs. Bill Gates lurks, with ‘the serum’, to finalise our enslavement. My trips to different leisure centre saunas in England have all involved overhearing this being discussed as though uncontroversial facts.

The artist and Haubenstock do in fact go mad like this, they riff out theories right up to a production of the antichrist (what was I saying) and as the book ends it seems they have gone too far, the speculative philosophising is too much for even the furthest out-of-the-box drone scientists.

Ultimately, I am left pondering whether I have experienced an eruption of historical trauma or the trauma of our current history. Whichever, I feel like I have been psychically stomach-pumped.

But the fact these books came out in 2019 and then the coronavirus crisis hit gives them a full geist glow. And under it all, repeatedly, obsessively, is the Cold War, and then WW2.

They are both utterly brilliant, perhaps essential, but they didn’t half pick their moment. And then, 2022. And then 2025: Please, wipe my brain clean and send me to an infinite Lake District of the Soul.